The ‘Global Flood Year’ of 2019 may be the new norm and we are not ready, IMPC researchers say

Researchers call for change in flooding research and management practices amid concerns of increasing disastrous flood events around the world.

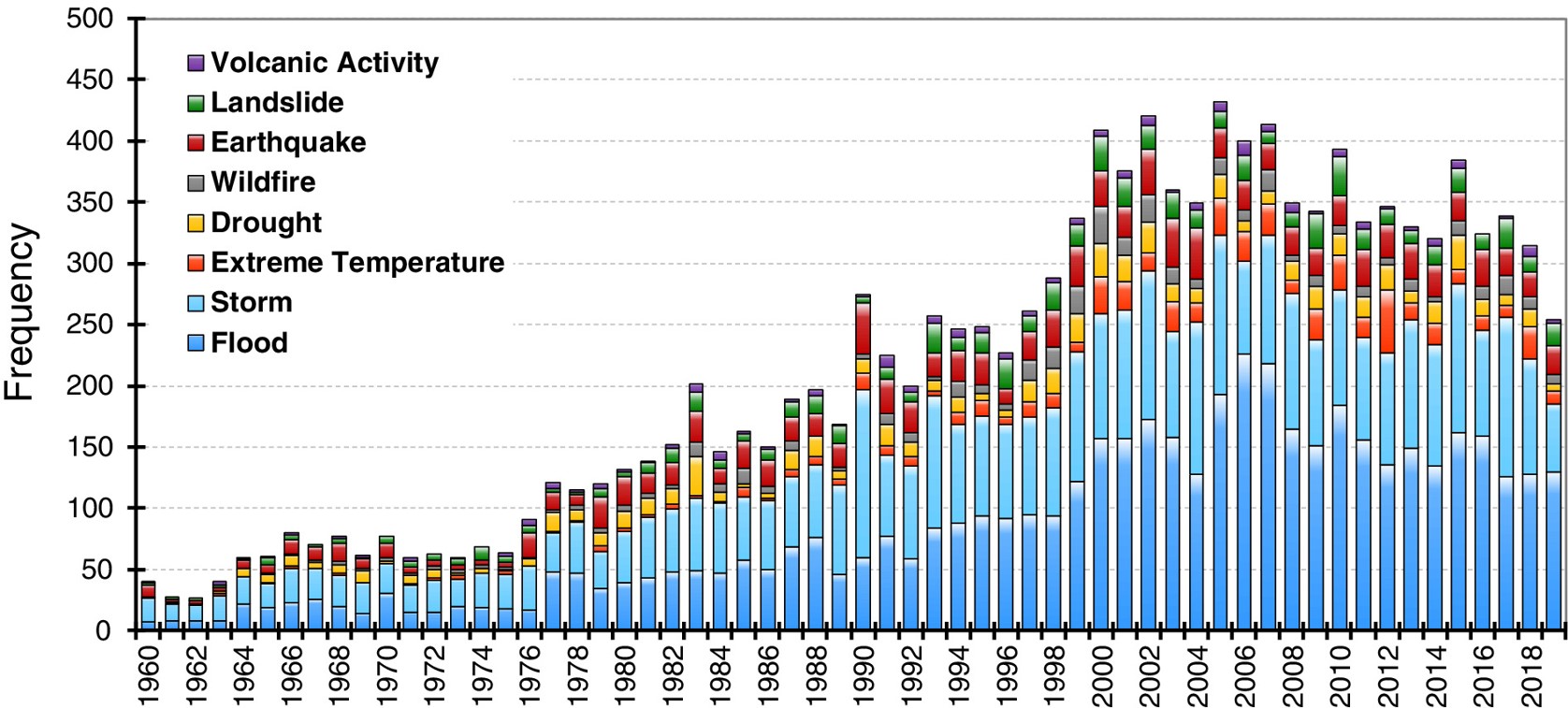

By Laila BalkhiFlooding has become the most common natural hazard globally. In Canada, it is also the most costly natural disaster. Prediction tools and methods have improved with scientific advances, but they are still not enough to account for the complexity of flood risk loaded with uncertainties of a changing climate and an ever-evolving landscape.

A transdisciplinary team of experts, including a hydrologist, a geographer, two engineers and an economist, highlighted emerging challenges of increasing flooding in various regions around the world. They particularly emphasized that the way flooding research and management is traditionally carried out in silos is just not enough to prepare for floods that are becoming more and more complex to predict.

Lead investigator of the Integrated Modelling Program for Canada (IMPC), Dr. Saman Razavi explained, for example, that “the concept of ‘return period’ typically used for flood risk assessments is grounded in stationarity – it’s a concept which assume that natural systems do vary but only within certain limits. And we’re finding more and more with our water systems that that’s no longer true. Even if we assume that return periods are ‘non-stationary’ and deduce that the one-in-25-year flood now could become a one-in-5-year flood in the next decade, that still doesn’t capture the deeper uncertainties and complexities of flooding research.”

These researchers call for a new paradigm of more transdisciplinary and cross-sectoral research approach based on scenario development and public engagement that accounts for the unknowns and complex nature of the Anthropocene floods.

Annual frequency of disastrous floods across the world has been the largest among all types of natural hazards and increasing over time. [See source]

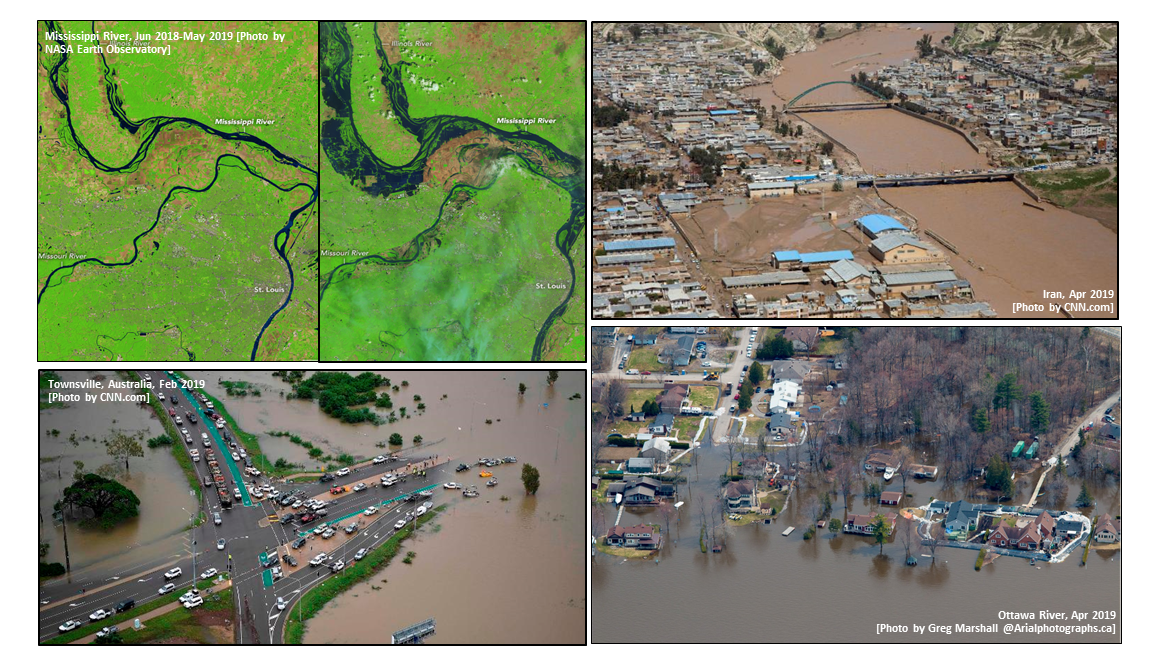

They specifically reviewed the disastrous impacts of last year’s flooding in Canada (Ottawa River), USA (Mississippi River), Iran (31 provinces), and Australia (City of Townsville) that caused billions of dollars in total damages and several human fatalities. Another commonality, besides the casualties, is that all these floods raised widespread public concern over how effective our infrastructure and operations management systems are in protecting societies.

Australians wondered why huge amounts of water were released from the Ross River Dam. Iranians wondered why their reservoirs were not enough to protect them in various provinces. Canadians raised questions on how reservoirs are operated on the Ottawa River, and residents in the United States went as far as blaming the US Army Corp of Engineers for mismanagement of hundreds of reservoirs.

“These concerns are actually rooted in deeper issues with the way we’ve done flooding research, infrastructure development and land-use planning. They all have an effect on how we determine flood risk and also on how people perceive it” said Dr. Razavi. Climate, urbanization, water control operations management, policy and land-use changes that happen over time all have a compound effect on flood risk, and each add on more uncertainty into future predictions.

Modelling tools have not yet been able to capture these multi-dimensional human-nature interactions with their trade-offs well enough to predict flood risk accurately. Therefore, flood research needs to expand its engineering-focused approach to more integrated cross-disciplinary approaches. But the effort should not stop there.

Integrated assessments of flood probability and risk need to be developed for various alternative future scenarios by consulting with a range of stakeholders, including policy-makers and communities, according to the researchers.

The researchers are hoping that this form of “soft” engineering becomes commonplace in flooding research and management to better prepare society in dealing with natural hazards.

Read more on these researchers’ published commentary by following this link or the citation below.

Citation: Razavi, S, Gober, P, Maier, HR, Brouwer, R, Wheater, H. Anthropocene flooding: Challenges for science and society. Hydrological Processes. 2020; 1– 5. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.13723

The Integrated Modelling Program for Canada (IMPC) is a transdisciplinary research program bringing together scientists and stakeholders from six Canadian universities, twelve government agencies and more than ten end-user communities. This team provides a unique expertise that integrates atmospheric science, hydrology and ecology with social science, computer science, economics, and water resource engineering. Explore IMPC Website to learn more.

IMPC is one of the 39 Global Water Futures (GWF) program, which is a University of Saskatchewan-led research program that supports leading-edge water science and aims to develop innovative decision-making tools to manage water futures in Canada and other cold regions. To learn more about the Global Water Futures program, follow this link.