The Search for the Perfect Flood

Working together to build a deeper relationship with the river

Tim Jardine

Associate Professor, School of Environment and Sustainability University of Saskatchewan

Solomon Carriere

Cumberland House Wilderness Guide

The tree was as big as a battleship. Most people would just watch it float by with admiration, but not Solomon Carriere. Within thirty seconds the trapper and champion canoeist was out the door and in his boat, racing the river current to catch the tree and board it! I still have no idea what he was looking for, but this was his way of getting a closer look at what was happening with the river.

We were at Big Eddy Lodge, a local trapper and a university scientist learning together about how the Saskatchewan River Delta works. We were searching for the perfect flood. I was there to prepare an instrument for water quality and release it onto the River.

In past times the Delta flooded, and the wildlife were adapted to those floods. In turn, the people who live there were also adapted to those floods. Now we are trying to recapture what those floods are; features such as when they happen and how big they are.

The Saskatchewan River Delta is big, important but vulnerable to upstream development. Hydropower dams have changed the way the water flows and how it effects the Delta ecosystem and its people. Solomon Carriere has seen these changes first-hand through a lifetime of living and paddling through the Delta. I’ve been learning from Solomon for the last ten years. We’ve spent time together on the Delta through floods and droughts. Before I met Solomon I thought that floods were good for ecology and bad for people. Now I know that the opposite can sometimes be true. Solomon knew that natural floods were good for the Delta but they can come with consequences: fish, birds, and mammals can all be harmed by unnatural floods that rise and fall quicker than they can adapt, dislodging trees from banks and hurdling them down river. But floods also create habitat for aquatic life, so we are trying to find that sweet spot where wildlife and people can thrive.

The question was asked, how can dam operators release water in a way that brings maximum benefits to ecosystems and people, while limiting harm? Water quality is one way that we are tracking effects on water level.

We had been waiting five years for the chance to use this instrument during a flood. The time had finally come. Little did we know that five days later, our instrument would be taken out by another large tree and swept away downstream to crash into a bank. It turns out that the most important time to observe a river in flood is also the hardest time for science to measure.

This is why partnerships are critical. Solomon and others in the Delta community of Cumberland House have eyes on the ground. Working together allows us to see the Delta at times when science is incapable of doing so. This is referred to by Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall as two-eyed seeing. The co-learning journey together brings us closer to understanding that perfect flood, so water can be managed in a way that heals rather than harms.

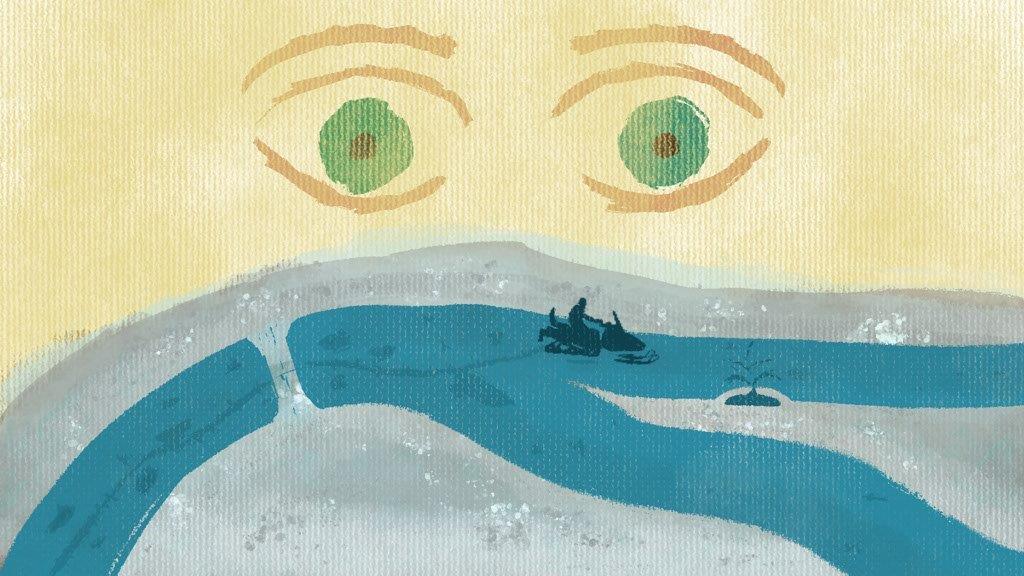

Both Eyes on the Ice

Investigating a Hazard on the Slave River

Karl-Erich Lindenschmidt

Professor, School of Environment and Sustainability,

Member, Global Institute for Water Security

We were snowmobiling along the Northwest Territories’ Slave River. It was the end of January, the coldest week of the year at -60 Celsius. I had to duct tape my forehead and cheeks around the eyes to protect my face from the freezing wind while driving my snowmobile. My guide, a Metis elder and trapper, cruised ahead of me on his own machine. We were on our way to the Slave River to investigate a phenomenon that makes winter travel treacherous and sometimes fatal.

When we reached the river, my guide took out a small diameter ice drill, swept the ice cover clear of snow and began drilling. It didn’t take long for him to punch through the ice and strike an air pocket. A burst of air was released. When he kicked snow over the hole it immediately shot up, demonstrating immense pressure under our feet. He said to me, “These pockets are dangerous, especially on a cloudy day when you can’t pick them out from the snowpack due to lack of contrast.” Trappers and other local residents have been known to crash through on their way across.

This was my first encounter with air pockets and double layers of ice (slush sandwiched between two intact ice layers) in rivers. After returning from the field, I called up river engineers across the country to learn more, but no one had heard of air pockets. These phenomena appeared unique to the Slave River.

Over the course of four years of field trips my guide shared with me his knowledge of the river, and the challenges of living and working on this land. The Indigenous Knowledge he shared was invaluable as we investigated the formation of the air pockets. He told me that this is a new hazard for his community. Before the 1980s, local residents and migrating caribou traveled the icy river corridor confidently, like a highway. His words prompted me to look up historical river flows. Maybe this piece of knowledge would help explain why air pockets form. By looking closely at the record we could see that the variability in the river flow at freeze up increased around the 1980s. In the 1970s, a dam was built upstream of the elder’s community, regulating the rise and fall of the river. It made sense to us then. With large river flow fluctuations, air gets trapped and sandwiched between sheets of ice and slush. I suddenly had so many questions. Even after many years of studying Slave River ice phenomena, it became clear to me that we still have much to learn about the impacts of dams on northern rivers. The priority however, was to find the safest routes for people to cross. We needed a better picture.

Next, we acquired remote sensing imagery and calibrated it based on in-person observations from local Indigenous community members. This team effort allowed us to see 400 km of air pocket distributions along the Slave River. From the sky these pockets dot the river’s main channel in a multitude of bulges and dents. This project since ended but we connect with the community through a multi-stakeholder network called Delta Dialogues.

This guide and I had developed a trust toward each other’s ways of knowing. Listening to Indigenous Knowledge showed me a new river ice feature, and trusting it allowed me to investigate safely. Likewise, my guide -now research partner- has become increasingly trusting of remote sensing imagery. With it he can plan safe routes around ice pockets, travelling farther than before to access remote trap lines and follow the caribou. To me, this was a good example of two-eyed seeing. Looking with Indigenous Knowledge through one eye, and western science through another, allows us to better focus on solutions with clearer vision.

For a video of compressed air escaping the Slave River ice, click here

To learn more, see...