Putting Indigenous knowledge at the forefront of water research in Canada

MISTAWASIS NÊHIYAWAK – In an attempt to create a better water future for everyone, Indigenous water experts and Knowledge Keepers have created a protocol that puts co-generation of research at the forefront, and promote its use across Canada in future water research projects.

By Mark Ferguson

The Everyone Together: Water Gathering Statement was created by a group of 22 participants representing 14 different First Nation and Inuit communities and organizations. The protocol outlined in the document was initially discussed over three days in April 2023 during the University of Saskatchewan (USask)-led Global Water Futures (GWF) - Mistawasis Nêhiyawak Water Gathering, and is now available publicly.

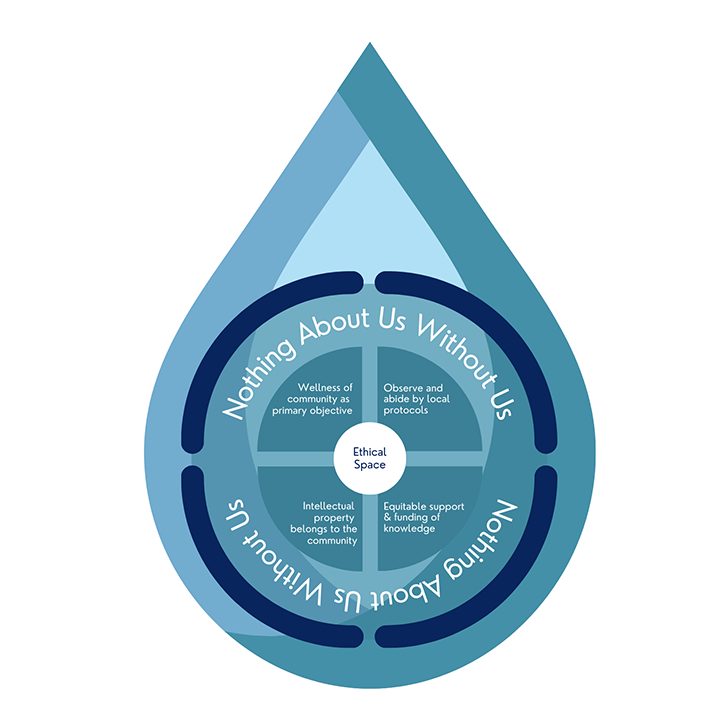

“Nothing about us without us,” said Anthony Blair Dreaver Johnston, Knowledge Keeper with Mistawasis Nêhiyawak. “Research must meaningfully engage community members, governments, organizations, and include local and traditional knowledge about the nature and use of water. This is how we grow as people and communities to be better stewards of the land.”

Johnston, a member of the GWF Indigenous Engagement Committee (IEC), said he has seen the impact that co-creation of knowledge has on empowering communities and developing effective research methodology through projects he has led alongside friends and colleagues with other communities’ non-governmental organizations, GWF, and USask.

“We have a responsibility to design research as stewards of our land, waters, and peoples,” said Johnston. “We envision a future where research is led by Indigenous communities and is responsive to their needs, centres Indigenous Knowledge, and helps to grow healthy water, relationships, and communities.”

Johnston said the water gathering statement outlines four areas that will help support the vision of the protocol:

- Prioritizing wellness of communities

- Observing and abiding by local protocols

- The need for equity in supporting and funding knowledge

- Keeping intellectual property with the communities

Johnston added that a younger generation will ultimately see impacts on the land from the decisions made today, and acknowledged Mistawasis youth Jenna Daniels for her dedication to the future of her community as one of the hosts of the Indigenous Water Gathering.

Creating a co-generation protocol was an outcome that researchers with GWF, the world’s largest university-led freshwater research program, had hoped for.

“GWF is a hugely ambitious undertaking across Canada that could not have become what it is today without the support of our Indigenous Engagement Committee and the many, many Indigenous partners and researchers that are part of the program,” said Dr. Corinne Schuster-Wallace (PhD), USask professor and associate director of GWF. “To make meaningful progress, the research framework outlined in the Everyone Together protocol is essential.”

Schuster-Wallace, liaison to the GWF IEC, pointed out that the effects of climate change are hitting Canada, and particularly Indigenous communities, even more than other parts of the planet, and that this summer alone we have seen more forest fires, hotter temperatures, severe droughts, and floods than ever before.

She thinks the protocol will help guide water research in Canada and around the world during this time of rapid change.

“We are at a critical time where we all must come together if we want to secure a water future for everyone,” she said. “On one hand, we have increasing water-related crises, but on the other we have centuries and generations of water and land stewardship based on Indigenous science and a concept of wholism and interconnectedness that Indigenous Peoples have used to maintain balance between people and nature. This gives me hope.”