Knowledge Mobilization Lessons from the Inaugural GWF Annual Science Meeting

The inaugural GWF Annual Science Meeting provided a unique opportunity to build relationships for the co-creation of research methods and outcomes that are more responsive to water and climate decision-making needs in Canada.

By Stephanie Merrill and Sarah FoleyJohn Pomeroy, GWF Director, and Phani Adapa, Director of Operations talk to Elan Henhawk, Elder of the Six Nations of the Grand River.

The inaugural Global Water Futures (GWF) Annual Science Meeting (ASM), recently hosted by McMaster University and Six Nations of the Grand River, was a momentous occasion for the GWF program. The gathering brought together the expansive pan-Canadian network of researchers and students for a stimulating science agenda and relationship-building for the co-creation of research methods and outcomes that are more responsive to water and climate decision-making needs in Canada.

While the Knowledge Mobilization (KM) Core Team is usually the messengers of the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of good knowledge mobilization processes for GWF research teams, we thought that hearing the needs and expectations of decision-makers, practitioners, and communities would be exponentially more fun and effective. The ASM was a perfect opportunity to hear the voices of Indigenous leaders and community members at Six Nations through teachings that included land-based knowledge exchange sessions, and a Partner’s Panel of water practitioners representing industry, government, and Indigenous and non-profit community stewards. Our generous hosts at Six Nations and our KM workshop guests provided valuable insight into both the theory and practice of good knowledge mobilization for impact.

Here are 5 KM lessons that emerged for researchers, students and staff to keep in mind as GWF projects progress.

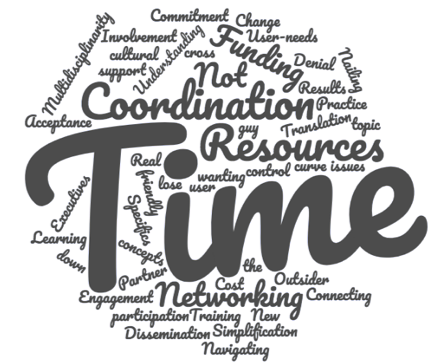

1. It takes time: There are no shortcuts to good research ethics.

A reoccurring message was the time and trust required to build, maintain and grow relationships. Successful knowledge mobilization is dependent on personal and professional relationships, and willingness to take the time to understand the history of your partners and your relationship with them is part of a long-term commitment between researcher, practitioner and community.

The needs of practitioners, communities and researchers must be integrated through co-creation, with recognition of the compromises that might need to take place. Different research and on-the-ground decision-making timelines must be a consideration when formulating a research project. Diversifying the definition of research success can help align researcher and practitioner timelines. Measures such as academic publication are important, but these need to be expanded to include research impact and uptake by practitioners, which can take a lot more (or less) time than the funding cycles for researchers. Creating both academic and user-oriented products are important to communicating the value of research to the academic and public spheres.

KM activities may not be enough to foster trust if they are exclusively conducted within academic institutions and systems. Expanding the accepted means of knowledge creation beyond Western scientific standards will facilitate trust and meaningful participation. A perfect example was our adventures out of the lecture hall and into the Six Nations’ community for cultural teachings, getting on the river, playing games, and sharing laughs, food and music—shared experiences that are key to relationship building.

For research with Indigenous communities, knowledge mobilization is fundamental to upholding good research ethics.[i] The research project must deliver results for both the researchers and communities that invest time and emotion in the process. Researchers need to work to privilege Indigenous knowledge and traditions in research projects with Indigenous communities. Participation without acknowledgement and redistribution of power is a meaningless and frustrating task for partners.[ii] Shared planning, action, interpretation and decision-making responsibilities, facilitated by two-way communication and accountability, will help ensure meaningful participation. These processes, though challenging, are vital for the creation of salient, credible, and legitimate results from a research program.

2. Uncertainty vs. Reliability: Cutting-edge isn’t always enough.

On the ground, confidence in the reliability of information for practical operations and decision-making can be fostered through both scientific rigour and stakeholder involvement in processes and interpretations.[iii] Cutting-edge science for the sake of curiosity and innovation is great for the vitality of academia and often good intentioned. But for practitioners, who need to make decisions quickly and within constraints, reliability can be more important. Uncertainty in science can never be eliminated, only managed, [iv] and knowledge mobilization provides the interactive dialogue necessary to set mutual expectations between partners. It is challenging to integrate partner expertise but addressing this challenge will provide better results that are more likely to have real impact.

3. Planning and Design: There is no recipe.

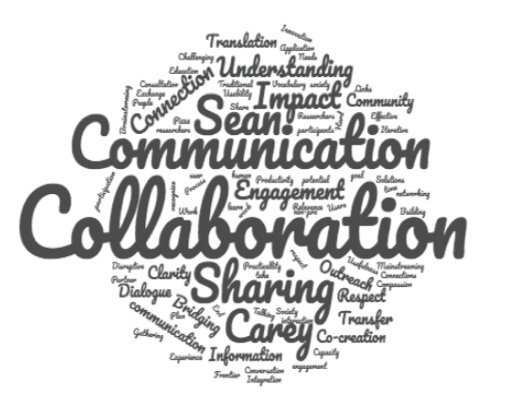

The processes of communication, collaboration, and sharing are as variable as the array of perceptions of what knowledge mobilization means (see image, right). Partners can communicate their advice and expectations of knowledge mobilization, but at the end of the day there is no exact recipe for how to do it. KM activities and their success will depend on the project and the needs and expectations of all partners involved.

Adaptive management of a project, to learn from past and current experiences to achieve better outcomes, will refine the recipe of knowledge mobilization as the project unfolds. Formally co-creating and documenting agreements for roles and responsibilities in the project are important mechanisms to identify expectations, respond to changes and revisit plans—only then do you have benchmarks for measuring success and timelines for evaluation of progress, such as asking your partners if they feel meaningfully engaged, and make changes to the planned activities if they don’t. Put it in your work plan, or plan not to do it.

4. Sharing: It goes both ways.

Good KM is a two-way process of sharing, agreement and trust building that should provide benefits to everyone. The responsibility is not solely on researchers to ‘do’ knowledge mobilization, and those who need to make more informed decisions shouldn’t just wait for knowledge mobilization to happen ‘for’ them. Researchers need to be open to contributions on research questions, methods and products and partners need to fully engage in the process, communicate their needs and expectations, and follow through on commitments. It is also important that researchers communicate the limitations of the scientific process and research outcomes, and that partners are understanding and receptive to how science can or cannot be applied. We can all work on better co-creation so research has meaningful impact.

The importance of interpersonal communication skills in knowledge mobilization cant' be understated; as a researcher, being outgoing and relatable is a great asset. But it is not vital. Showing up and doing the work with your partners consistently, mindfully, and with a genuine interest in your partners’ circumstances and needs is just as valid and effective in generating impact and maintaining good relationships.

5. Support and Resources: You’re not alone.

The GWF KM Core Team is in place to support researchers in their aims to address challenges and identify opportunities. We can assist as projects identify and engage partners, develop and design projects, interpret and communicate results, and evaluate success. Call or email the KM specialists any time, we are dedicated to guiding and assisting you and your research team.

There is a new website of resources provided by the KM Core team where we have posted guidance documents, templates which can be adapted for particular project needs, and further reading. A List of Services is also available, outlining the activities that constitute KM and the KM Core Team’s support capacity. If you want something that’s not yet there, please let us know.

The KM Core Team is calling on research team members to participate in a KM Champions Network, where we will gather regularly for team problem-solving, success sharing, and capacity building. Join up by emailing any of KM specialists. We will convene our first gathering soon!

Acknowledgements and Thanks

Thank the organizers and hosts at Six Nations of the Grand River for the invitation for GWF to spend time in your community and hear from elders, leaders, members and scholars. It was an inspiring and educational visit and the beginning of a better relationship. Thanks to Katrina Hitchman of the Canadian Water Network for sharing their 15-year National Centre of Excellence’s academic-practitioner KM lessons, and to the guests of the KM Workshop Partners’ Panel for their generous time and valuable advice:

- Wayne Jenkinson, Senior Engineering Advisor, International Joint Commission

- Sandra Cooke, Senior Technical lead for water quality and Chair of the Water Managers Working Group, Grand River Conservation Authority

- Michael Vieira, Hydroclimatic Studies Engineer, Water Resources Division, Manitoba Hydro

- Amber Skye, Mohawk and of the Wolf Clan of Six Nations of the Grand River and Health and Behavioural Science Expert, University of Toronto Dalla Lana School of Public Health

Stephanie Merrill is the GWF KM Specialist based at the University of Saskatchewan and Sarah Foley is a GWF KM Core Team summer student in her 4th year studying environmental biology and political studies at the University of Saskatchewan.